On a personal basis, my biggest event of 2020 should have been my long-planned orthopedic surgery. I prepared for this operation for several years and never expected it to be overshadowed by a global pandemic. But instead of a quiet recovery, I joined the global lockdown at home with my family like millions of others, running after my children on crutches while my wife was working from our guest room.

The lockdown allowed me to do a fair amount of reading and thinking about the implications of this unprecedented crisis on cities and mobility. This article covers my reflections on people and goods transportation under new health and safety norms and offers several thoughts on the key enablers to operate a much-needed shift to sustainable urban mobility.

During the crisis, I saw the reassuringly quick resurgence of local communities, the power of public-private collaborations, how different governments approached citizen responsibility and, finally, the rise of cities' authorities in managing the crisis. With the safety and health of people as the main driver, these trends and the general state of disruption constitute an historic opportunity for change, as shown by the growing number of pledges to build back better post-COVID-19.

As many countries now begin to open up, people and organizations focus on what the “new normal” will entail. The COVID-19 global pandemic has and will change people’s lives and how cities and businesses operate. The “new normal” will call for unusual practices from companies and regulators to protect employees from potential infection as we learn to live with the virus in our midst, to produce strategies to stabilize economies and to trigger innovations to drive sustainability under higher health and safety standards.

Equally, this is a pivotal moment for each company to demonstrate responsibility towards society by deploying all its care, critical know-how, reach and resources. When it comes to urban mobility, this is a critical point for business and city leaders to embrace collaboration. Together they can prevent a transport crisis that would further hinder recovery and avoid the future perils of “business as usual”. Simply put, they should prevent a rush to single occupancy driving (i.e. personal cars) and promote a safe use of public transport and integrated multi-modal solutions which are crucial for creating optimized and sustainable mobility systems.

This is important, because the vast majority of our existing transport infrastructure simply can’t absorb traffic under the new COVID health and safety requirements, not to mention the mental barrier they imply.

By establishing new public-private collaborations and leveraging the latest technologies and knowledge in data-sharing, cities and businesses can use this crisis to transform their mobility systems and lead the way to new shared-value creation. Such actions will not only address the current crisis but also pave the way for achieving the SDGs and the climate goals outlined in the Paris agreement.

Digital Mobility Service Providers (MSPs) have proved their relevance over the last 10 years as an alternative to traditional mobility solutions with high user acceptance. We see many cities now convening local MSPs or transport operators to aggregate the know-how to answer the new challenges of urban mobility and activate a “local mobility ecosystem”.

The next step would consist in establishing mobility-related coalitions to create and manage new models for the movement of people and goods, and the implications on the use of space. Each of these coalitions would gather their local mobility ecosystem players and the key private and public stakeholders that can influence the movement of people or goods.

The people mobility coalition, a collaboration between the local mobility ecosystem, business and the authorities, will have the objective to enable efficient and clean transport while preventing the spread of the virus. The natural first step would be to coordinate commuting patterns which we can call “access policies” to create new access policies aiming at spreading commuter’s trips over time, reducing the risk of virus transmission and safely managing the flow of people within infrastructure capacity.

For example, the coalition could coordinate the implementation of the (most probably) permanent measures of teleworking, so that group A of companies allow teleworking the first two days, and group B the last two days of the week. The coalition could further coordinate starting times in schools by districts so that all families in one sector of the city would travel at a certain time before another sector does or before students and older professionals do.

The new access policies should be consensus-based and promote criteria like social integration, emergency response or the criticality of trips while leaving a degree of flexibility to share responsibility with citizens. Deploying these rules would ideally coincide with a widespread and coordinated approach to teleworking and the opening of new co-working spaces as part of an agreement amongst leading local businesses of the coalition.

The coalition dealing with the mobility of people should also consider ways to change commuting behavior. The immediate objective is to prevent single occupancy driving and promote shared multi-modality with measures ranging from public transport incentives (under high hygienic and distancing standards) to stricter measures to reduce access to city centers or main corridors for single occupancy vehicles. Digital applications for tracing infected people planned in many countries could make safe car-sharing (or public transport) possible. It is very timely to implement access restrictions at the end of lockdowns as there is less traffic and people are more inclined to accept them and they could offer a revenue source for cities.

Behavior change is one piece of the puzzle, but the people mobility coalition should also address embedded inequalities in our transportation systems. A first step could be to assess existing travel zone boundaries and fare rate structures to make sure that disadvantaged groups can afford and are physically able to enjoy the benefits of connectivity.

Regulating access for motorized vehicles could be combined with measures encouraging active and individual mobility modes. We already see increased bike use which allows social distancing and safe travel while traffic is at its minimum. Cities are taking advantage of this trend to increase the number of bike lanes.

The coalition could consider incentivizing citizens whose commuting time is below the “ideal” access time (different for each city) to shift to active modes gradually. For example, collaboration with local businesses to provide a test fleet of shared electric bikes, cargo bikes or scooters to certain groups (and lanes for using them) will accelerate the adoption of clean modes of transport. Over time, this will answer short distance mobility needs at the local level due to the emergence of local community life and could help to crystallize new local economic hubs.

Regarding the movement of goods, the pressure on existing supply chains and the need for more efficient and resilient urban deliveries should lead the local logistics stakeholders to consider new operating models. One immediate opportunity for a goods movement coalition is to coordinate policies on time and curb-space usage for urban logistics to manage the existing capacity of the road infrastructure. For example, using the “new access policies” mentioned earlier could allow coordinating deliveries while preventing congestion.

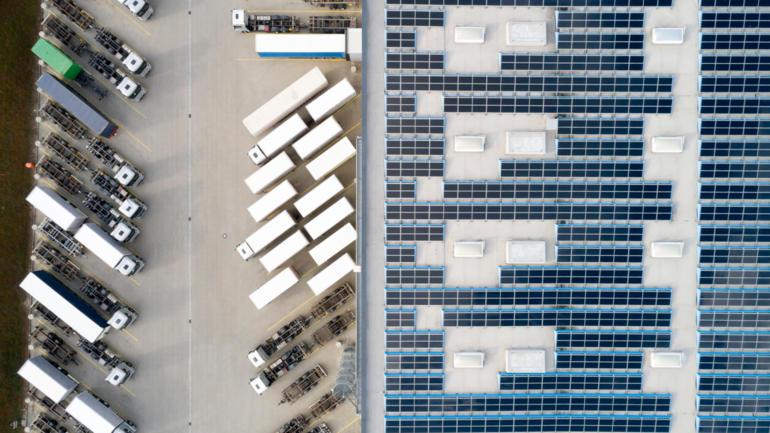

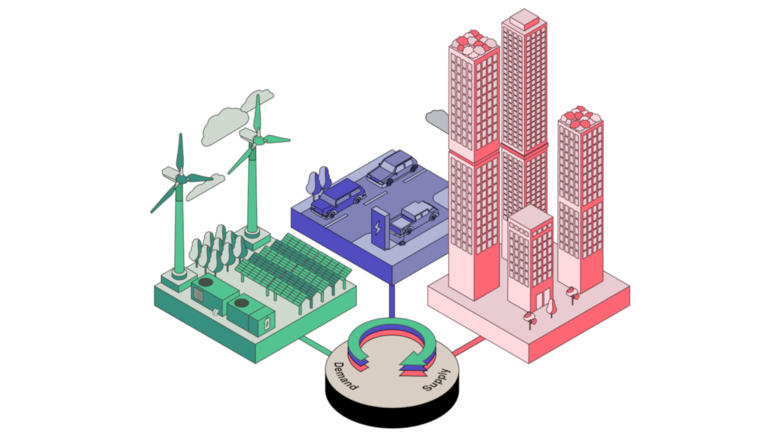

Another way to achieve efficiency and resilience would be to mutualize several vehicles for deliveries – we have seen examples of this for medical supplies. This could be done by creating an aggregation platform that would gather the demand for packages to be delivered across several operators, and manage the capacity of vehicles available and their routing. Several examples exist on how to manage such a platform, set the parameters and share the financial benefits across members; and companies have developed expertise in optimizing large fleets with complex patterns. The goods movement coalition would also be a platform to accelerate existing electrification plans (vehicles and infrastructure) and delivery infrastructure implementation (i.e. shared warehouses and delivery lockers). At WBCSD we are already taking action to support and unify business around increased electric vehicle (EV) deployment. Just last week we launched a new comprehensive guide for corporate EV adoption.

Achieving impact and allowing operations for some of the measures mentioned earlier requires cities to look at two enablers: the management of space and the digitalization of mobility.

As a first enabler, the people and goods mobility coalitions would communicate with a dedicated space management coalition containing experts in urban planning, land management and real estate public and private participants. This group of experts should actively coordinate and answer the needs for space to enable the changes emerging in new mobility patterns. As seen before, the immediate need is to create new bike lanes to allow safe cycling and accompany the active mode incentives. Documentation is readily available on how to create pop-up lanes before going for more structural changes to the infrastructure.

Another opportunity for space management may arise with the economic downturn following the COVID-19 confinement. Many local (and global) businesses will look for alternative revenue sources and costs reductions. As owners or tenants of space, they have an opportunity to rent or re-use their space to satisfy emerging needs from the new mobility patterns outlined earlier.

For example, a local restaurant or hotel could rent its space for co-working to teleworkers who cannot work from home or are on the move. These businesses may well have a parking spot or a garage that could also be used as a docking space for shared bikes or scooters, thus creating a mobility hub.

The same may happen over time with high-value city-center office space, which companies will quickly see as unnecessary expenditure when teleworking has made its way into working habits. This space could enable new urban logistics practices such as delivery lockers or shared warehouses, or even create housing projects contributing to reducing urban sprawl in the longer term.

The second key enabler is the digitization of mobility. Considering that data-sharing at the city or regional level may be essential to realize stricter public health and safety norms, this is about accelerating digitization by applying it to transport.

This critical capacity will guide decision-making in use cases like the creation of a Mobility as a Service (MaaS), implementing the “new access rule”, urban logistics efficiencies, city fleets management or new space allocation. The data-sharing capacity should be created by the local mobility ecosystem and operated by a neutral entity to ensure trust from the public and allow a sound balance of influence from public and private players forming the ecosystem. Within our Transforming Urban Mobility project, we are now working with our members and partners to inform policy making and regulatory actions necessary to help unlock the true value of data by enabling data-sharing to create public and private sector benefits.

To conclude, we’ve looked at a pathway based on collaboration and technologies to provide transport solutions and make mobility more sustainable. In many ways, the COVID-19 crisis has shown that change is not only possible but inevitable.

I believe we have a collective responsibility to address this crisis while avoiding the next one. Now that nations are starting to lift their lockdowns, it’s time for business to take part in the conversation too and show its capacity to innovate and implement action.