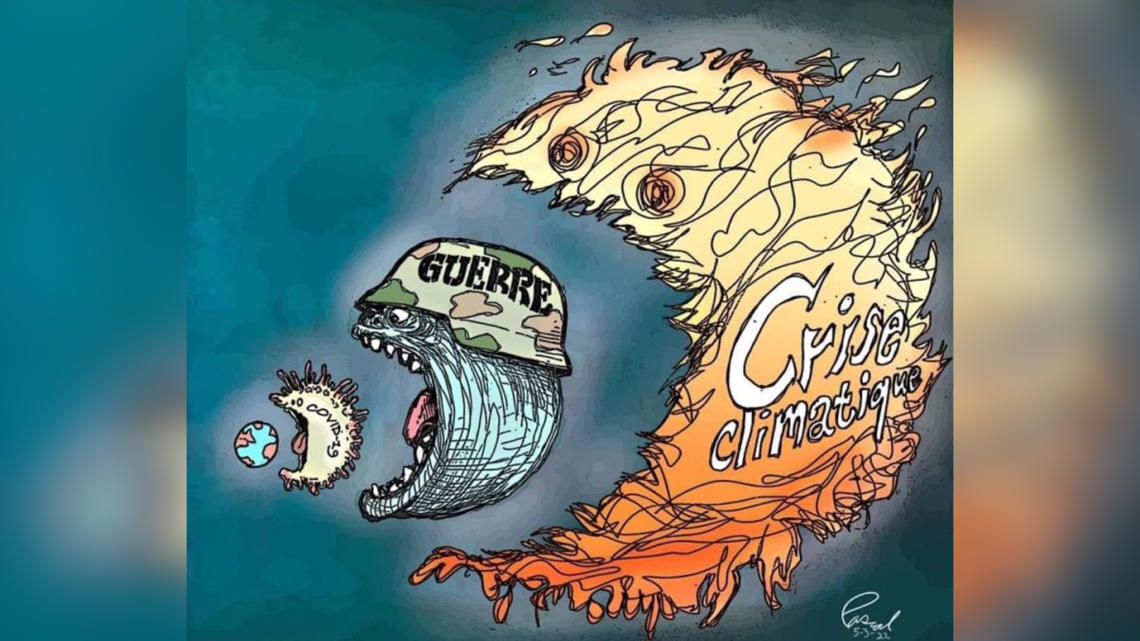

Just when we thought the COVID pandemic would start releasing its pressure on the global food and agriculture systems, a litany of social, natural, and climate issues have again exerted tremendous force upon them. The war in Ukraine is having significant consequences on energy and food markets, the new report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows dramatic predictions for climate and nature, and a host of alarming climate news includes ‘extraordinary’ heating in polar regions, forecasts of heatwaves and drought in Southern Europe and a prolonged ‘megadrought’ in Western US.

The war in Ukraine is leading to a surge in global prices of wheat, maize and vegetable oils. The countries most impacted by this rise are the ones that rely heavily on food imports to feed their populations, such as the Eastern and Southern Mediterranean as well as sub-Saharan Africa. But in Northern countries too, many people worry about food security, and argue that today’s global import shortages require increasing their own agricultural production. Furthermore, some speak up to put environmental and health concerns on hold while focusing on producing more.

Looking back, the « feed the world » narrative has been in existence for the past 50 years. But while it held probably true at times in the past, the planet is not short of food anymore. On the contrary, according to the United Nations, the world produces about a one-third more than the nutritional needs of the global population. The surplus is even higher if we add that almost half of cereal production is used in animal feed, and to a lesser extent to produce biofuels - this while the richest countries overconsume animal products far beyond nutritional needs, to the detriment of health and the environment. The dilemma is that we produce way enough food to feed everyone, yet world hunger has been on the rise for the past five years, a historic change in trend after decades of too slow a decline. The planet has never produced so much per person, but 700 to 800 million people are too poor to access food. The challenge really is thus not to produce more, but to distribute fairly and equitably.

While some stakeholder groups in Europe argue that we should increase European agricultural production now because the war is on Europe's doorstep, many argue that a much bigger threat is on the doorstep of Europe and of the world: today’s agricultural production systems are putting our Earth beyond its planetary boundaries, which is in turn threatening humanity much more than the war in Ukraine: biodiversity is collapsing, climate change is accelerating, pollution (fertilizers, pesticides, plastic) is worsening, nutrition and health are deteriorating.

It would be a terrible mistake for the world to pretend that it is avoiding food crises in Africa and the Middle East by reviving and expanding Northern industrial agricultural production.

A mistake, firstly because the cultivation of Northern countries areas dedicated to biodiversity, which would be disastrous from an ecological point of view, would have only a very marginal role to compensate for the reduction in global supply. Much larger volumes could be generated by policies to rebalance the production of proteins across animal and vegetal sources, as well as to reduce the production of biofuels from cereals and oilseeds.

An enlightening piece from the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI) clearly expresses this:

"As Europe cannot hope to produce more, it is only by reorganizing its food system as a whole as the (European Union’s) Farm to Fork (F2F) is trying to do, that it will be able to increase its contribution to the world food balance. (...) Because our consumption of animal proteins is almost double that required to cover our nutritional needs, EU imports of soybeans and sunflowers to feed industrial livestock, the EU is now a net importer of calories: it depends on the rest of the world for 10% of its consumption. A 40% reduction in the consumption of animal products, and a transition to low-fodder and self-sufficient livestock farming, would thus make it possible".

Reviving and expanding Northern industrial agricultural production would also be a terrible mistake, secondly because it would continue to keep poorer countries in dependence of other countries' productions. Northern countries would be much more impactful in helping vulnerable countries in the face of soaring food prices on international markets by supporting food security support schemes managed by the World Food Programme, by financing existing social safety nets in these countries, and on the long term by helping them diversify their basic food, reduce dependence on imports, and develop production where possible at a reasonable economic and environmental cost.

Both the latest IPCC report and the conflict in Ukraine urge us to radically transform our food and agriculture system towards one that is more resilient in face of increased climate variability, geopolitical and trading crises, and that can become positive for climate, nature, and people (from farmers to consumers). Something that only regenerative agriculture provides, when it include all the elements of regeneration, like the framework adopted by WBCSD’s One Planet Business for Biodiversity (OP2B).

Let’s not miss this historical window of opportunity: that of rethinking our way of producing and consuming food, to reconnect us to ourselves, to others and to nature, in a fast-changing world.

This content represents the views of Alain Vidal, Independent Scientific Advisor to OP2B, which are provided for informational purposes only.